People Skills is a book by Robert Bolton in which he meticulously details different tools, attitudes and frameworks to get better at communication. The first chapter of the book deals with ‘roadblocks’ to communication [1]: particular behaviours that endanger understanding. Some of these, like ‘criticising’ and ‘ordering’ are pretty obvious. Some are less so, and even counter-intuitive.

The two roadblocks I find most interesting are ‘advising’ and ‘reassuring’. Each of these roadblocks is worryingly common. When I first read the book I recognised both behaviours in myself, and it’s been clear to me subsequently how worthwhile it is to avoid these roadblocks. Herein I’d like to expand a little more on each block, why it’s a problem, and what alternatives there are.

Advising: telling people you know best.

I was once staying with a friend, and one night we were walking home together from her place of work.

“I just can’t stand it,” she was telling me. “He doesn’t respect my authority, he’s constantly undermining me. He’s making it impossible for me to do my job, then blaming me when things go poorly.” It seemed like things weren’t going so great. Having read People Skills, and done a little communication training, I tried to be helpful, listening attentively and reflectively: “It sounds like part of the problem is issues around age differences.”

It was a good conversation, in that we were communicating well, and I like to think I was doing my friend a service in that my quality listening was helping her to grapple with her problem. Until I made a terrible mistake: “Why don’t you….” Almost immediately, I knew I’d said the wrong thing. My friend didn’t mind, but I hadn’t helped her at all: “No, that wouldn’t work, because….”

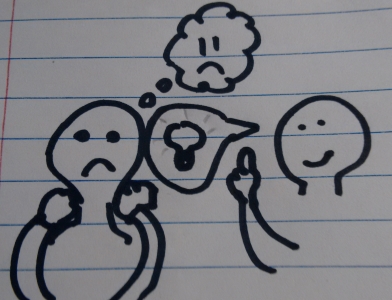

When you are communicating with somebody, and they have a problem, it’s tempting to feel that your role in the conversation is to fix it. Particularly when the solution is obvious to you, you want to step in, wave your magic wand, and help your friend out, right? That’s what friends are for. Yet, in fact, “advising” is a barrier to quality communication.

Firstly, advising is arrogant. Naturally, the speaker in the predicament understands it better than the listener. They know the history, the people, the relationships, the context. Of course, they communicate this through the conversation. But it’s unlikely that the listener know better, regardless of what other wisdom they may bring to the encounter. “The advisor”, writes Bolton, “is unaware of the complexities, feelings, and the many other factors that lie hidden beneath the surface.” Most often, the person in the problem has the resources themself to discover a solution. They don’t need it brought to them, they need a companion as they look for it.

Thirdly, sometimes people don’t actually want solutions. Sometimes someone is complaining about a problem, and all they need is for that problem to be acknowledged. Sometimes all they need is a hug. Sometimes all they need is for somebody else to say, “You’re not alone, I also cry over what Australia is doing to refugees.” To respond to a problem with a solution risks ignoring and diminishing another’s emotional needs, unfairly neglecting the other dimensions of their situation.

Reassuring: actually, it is that bad.

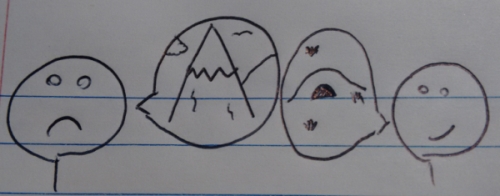

Once, a friend of mine got some bad news. I encountered her crying, looking fairly distraught. She wasn’t going to pass her course, she was going to have to do another semester of study, her plans for the next six months were in tatters. In this situation, one tends to offer reassurance: “Don’t worry.”

Reassuring is probably the most common response to another’s problems: “It’s OK”, “It will be alright”, “It’s not that bad.” The implicit message in this response? “You are over-reacting.”

If someone is upset, they must have a reason. Yet reassurance diminishes the significance of this reason, telling the speaker that their concerns aren’t actually well-founded: “It’s OK” basically means “It doesn’t make sense that you feel upset.”

Instead of reassuring, why not do the opposite? Rather than diminish someone’s concerns, validate and recognise them. Empathising with somebody in their moment of sadness – “That sucks”, “You must be pretty worried”, “God, that’s terrible” – let’s them know that you respect the way they are feeling and perceive their need for support.

Smooth driving here on in?

Only a small part of People Skills is dedicated to the twelve roadblocks. Clearly, simply being aware of and removing these two isn’t enough to make one an excellent communicator, and it’s not until later in the book that we begin to encounter positive behaviours that could be practised instead of advising or reassuring.

However, this section stuck with me. Perhaps because it identified existing bad practises, it made very clear to me things I was already doing that I could stop doing. This is mentally easier than imagining new behaviours! I’ve remained very conscious of these behaviours since, and when I do happen to lapse into one – as in the anecdote above – I’m reminded again of their problems.

So there is a lot to communicating well, and really, y’all should just go read People Skills in full. But seriously, the least you could do, get rid of that advising nonsense, and cut out the reassuring. Take it from me.

[1] Bolton’s book liberally compiles relevant work by others: the ‘roadblocks’ concept is Thomas Gordon’s, from Parent Effectiveness Training: The “No-Lose” Program for Raising Responsible Children. All twelve roadblock are listed here.

December 11, 2014

December 11, 2014

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

[…] my last post here, I wrote about roadblocks to communication. When listening, “advising” or “reassuring” can undermine good […]

[…] People Skills, Robert Bolton discusses assertion in detail (as well as roadblocks to communication and reflective listening), proposing a model, describing a process, and outlining considerations […]